A recreational runner, in a lengthy letter, describes their problems with pain in the left Achilles tendon, which has persisted for over a year. So far, they have tried various therapeutic methods, but none have provided relief. Recently, following a friend’s recommendation, they began a daily routine of special Achilles tendon stretching, where they rise on a step with the opposite leg and slowly lower themselves with the injured one.

Isolated eccentric contraction

Description

They feel the pain has decreased after a few days, but they are unsure how long to continue this stretching, how often to do it, and when they might expect further improvement or relief.

The technique they describe is called isolated eccentric contraction, first introduced and recommended as a therapeutic procedure in the early 1990s by the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. In short, experts at the institute observed that when patients with Achilles tendon inflammation underwent this type of focused stretching regularly and long enough, the need for surgical interventions at their institution decreased by 90%. Like any new idea, this one was initially met with skepticism and disbelief in the profession. I recall attending some conferences of that era, where Swedish experts’ presentations were met with laughter because entrenched beliefs prevented a broader perspective on this novelty in treatment. Suffice it to say, no one laughs today, and isolated eccentric contraction has become part of the conventional approach to treating chronic Achilles tendon pain—and not just that.

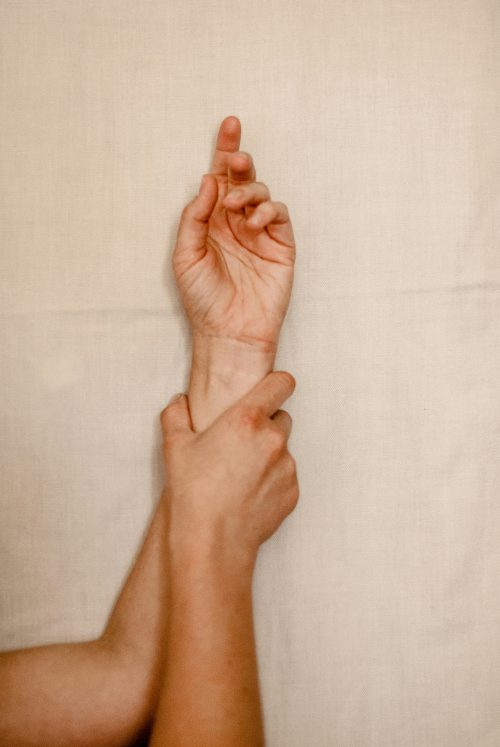

To better understand this technique, it is necessary to differentiate concentric from eccentric contraction. Concentric contraction means activating a muscle as it shortens, such as bending the elbow, where the biceps muscle lifts a weight by shortening. In eccentric contraction, as in the same example, when you want to slowly lower the weight to the ground, the biceps muscle tightens (to slow the extending movement) while simultaneously lengthening. Counterintuitively, eccentric contraction is actually the dominant way muscles are activated in typical movements. However, isolated eccentric contraction, as discussed here, excludes the concentric part of movement found in usual activity and focuses solely on the eccentric component through the full range of motion. In short, we aim for eccentric contraction along the full length of the movement at the maximum tolerable load.

Why is this beneficial?

Most tendons in the human body have a sheath or vagina (its Latin name). This well-lubricated sheath allows the tendon to glide efficiently, transferring forces with minimal friction while being separated from its surroundings to prevent interference or increased friction. Any obstacle to this gliding will cause a sensation of catching or pain, possibly accompanied by inflammation. Understanding the development of inflammation in tendon sheaths requires insight into one way the body adapts to daily or sports activities.

The body adapts to what we demand of it. If we lift weights and exercise for strength, the muscle will grow stronger and larger. If we are physically inactive, it will weaken. Flexibility exercises increase mobility, while sitting still or performing short movements makes the body stiff, and tendons become less mobile. This is an evolutionary adaptation aimed at conserving energy and tailoring the body to specific demands.

For tendons, this shortening occurs in three steps. First, the viscosity of the lubricating fluid increases. Second, the connective fibers that make up the tendon and extend through the entire muscle shorten. Finally, the tendon itself thickens. All this allows for shorter movements and slightly greater strength within a smaller range of motion. The problem with this adaptation lies in its temporary nature, as evolution intended it to be periodically interrupted by movements in the opposite direction—toward stretching, increased mobility, and longer eccentric contraction. When such counteractions are absent, the processes can progress toward further thickening, potential microdamage, and inflammation, which we perceive as pain. In short, modern life with its specialization in daily life, sports, and professions, puts parts of our locomotor system—tendons in this case—into states of shortening, overstrain, and pain.

For tendons, this shortening occurs in three steps. First, the viscosity of the lubricating fluid increases. Second, the connective fibers that make up the tendon and extend through the entire muscle shorten. Finally, the tendon itself thickens. All this allows for shorter movements and slightly greater strength within a smaller range of motion. The problem with this adaptation lies in its temporary nature, as evolution intended it to be periodically interrupted by movements in the opposite direction—toward stretching, increased mobility, and longer eccentric contraction. When such counteractions are absent, the processes can progress toward further thickening, potential microdamage, and inflammation, which we perceive as pain. In short, modern life with its specialization in daily life, sports, and professions, puts parts of our locomotor system—tendons in this case—into states of shortening, overstrain, and pain.

The solution is logical: do what hasn’t been done or has rarely been done. In this case, that is isolated eccentric contraction through the full range of motion, aimed at reducing the viscosity of the lubricating fluid, elongating the connective structures that comprise the tendon and parts of the muscle, and consequently healing the tendon’s thickening and promoting its recovery.

Such an intervention must be introduced gradually, be sufficiently intense, and last long enough (months) for the described biological changes to occur. For Achilles tendon issues, our experience shows that therapeutic results are achieved more quickly if isolated eccentric contraction is combined with general physical activity, which helps improve both local and global circulation, further enhancing the characteristics of surrounding muscles and connective structures near the Achilles tendon.

The tensional model (click for article) posits that no structure in the human body is isolated and separate from its surroundings but rather an integral part of a whole. An injury to one part of this system is merely a consequence of changes in other parts of the complex system. Thus, diagnosing other potential causes or triggers for tendon inflammation is a standard part of diagnostics at our Polyclinic. This aims to determine other interventions that could shorten rehabilitation and improve its efficacy.

Finally, are all tendons in the human musculoskeletal system suitable for treatment with isolated eccentric contraction? The literature and scientific research are not unanimous on this matter.

From our experience, foot and hand tendons respond particularly well to this method in physiotherapy. Tendons of the shoulder girdle react less effectively to the same stimulus. On the other hand, hip tendons, in specific cases, are excellent candidates for this therapeutic direction. The quadriceps tendon is a special case—not because it doesn’t respond well to isolated eccentric contraction, but because it causes undesired, excessive, and concentrated pressure on the patellar cartilage, which is typically an integral part of tendon inflammation in this muscle. This issue can be circumvented or mitigated, but that’s a topic for another discussion.